Along with streets and places such as Piccadilly, Leicester Square, and Oxford Street, Downing Street is probably one of the more recognisable London street names, not just in the United Kingdom, but across the world, given the number of tourists who peer through the gates that separate Downing Street from Whitehall.

Number 10 Downing Street has been home to the Prime Minister (or more correctly the First Lord of the Treasury) since 1735, when the house was given to Sir Robert Walpole.

There have been many gaps in occupancy by Prime Minsters, however a central London house was considered a benefit of the role. It was only in the early 20th century that it became a full time residence of Prime Ministers.

Security has long been an issue. It was not so long ago that the public could walk down the street, with the street finally being closed to the public in 1982, and in response to ever growing threats, security measures such as physical defences and armed police have been added and enhanced.

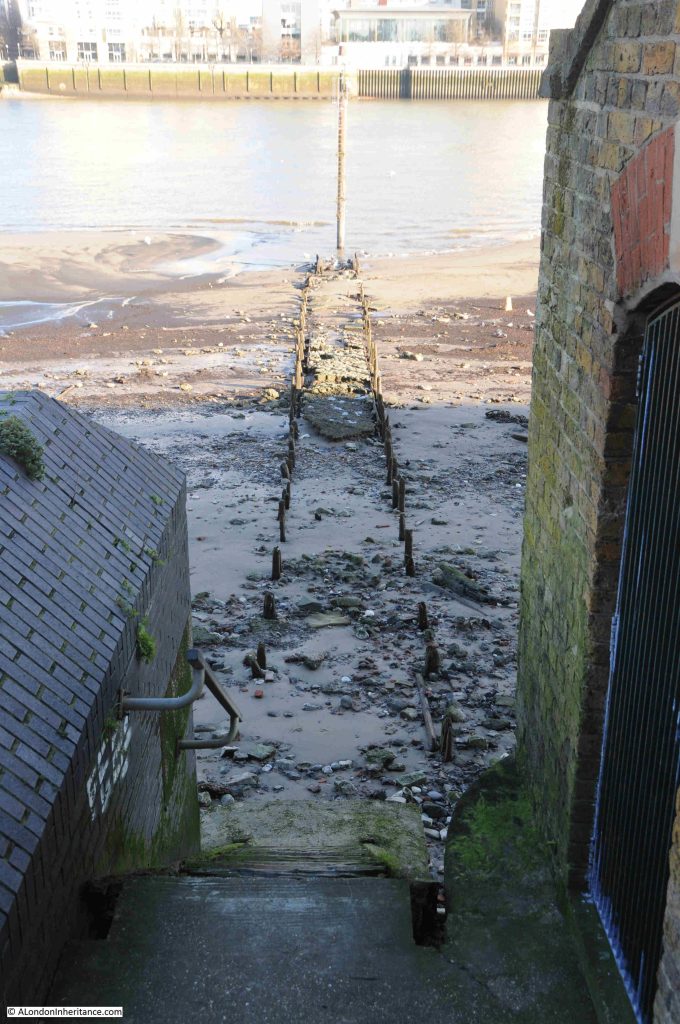

So today, this is the best view of the street for tourists and members of the public who do not have official business in any of the buildings and institutions that line Downing Street:

The street has seen so many Prime Ministers, newly elected, arrive in an atmosphere of enthusiasm and expectation, only to leave having been rejected either by the electorate, or through the actions of their former colleagues.

For a rejected Prime Minister, perhaps the most difficult way to leave is when you have been rejected by former colleagues. Those who once supported and worked with you, and with whom you had a shared vision of the future.

Whilst this must be incredibility frustrating, it is not as bad as the treachery of the person who was once the land owner and who gave his name to the street, who through his treachery, condemned former colleagues to the worst death penalty that the State could impose, convicted of being a traitor and being hung, drawn and quartered.

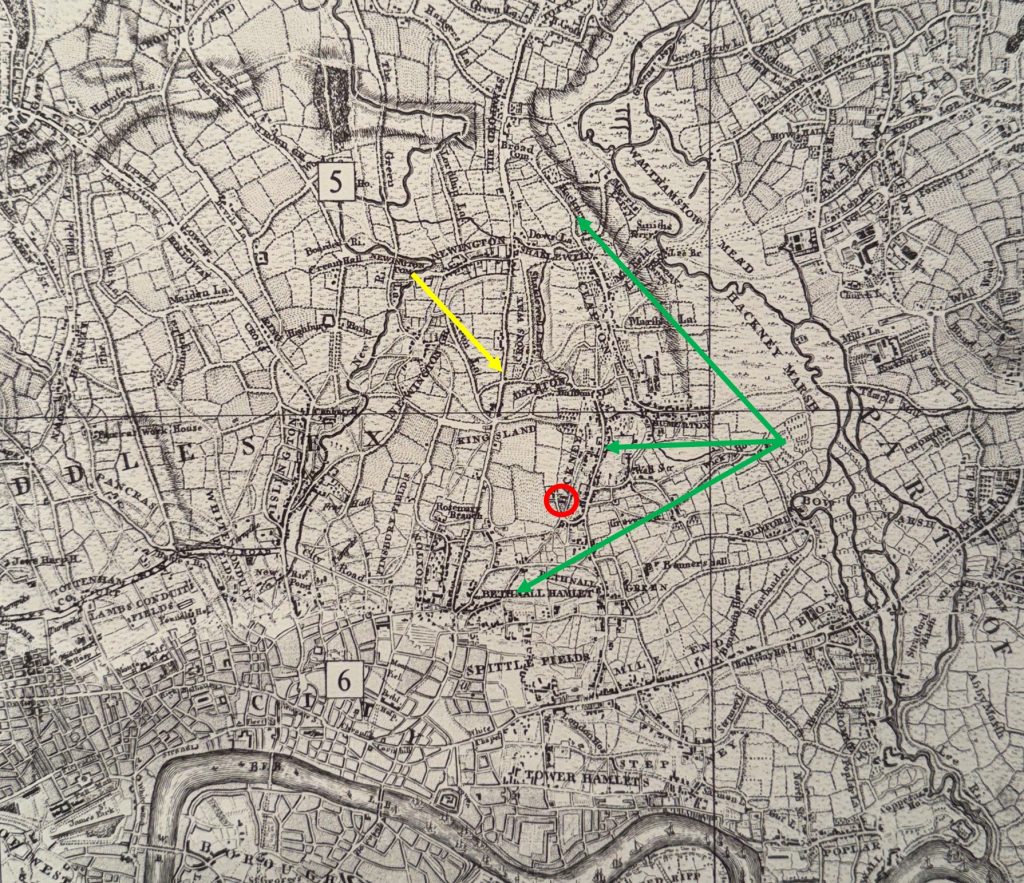

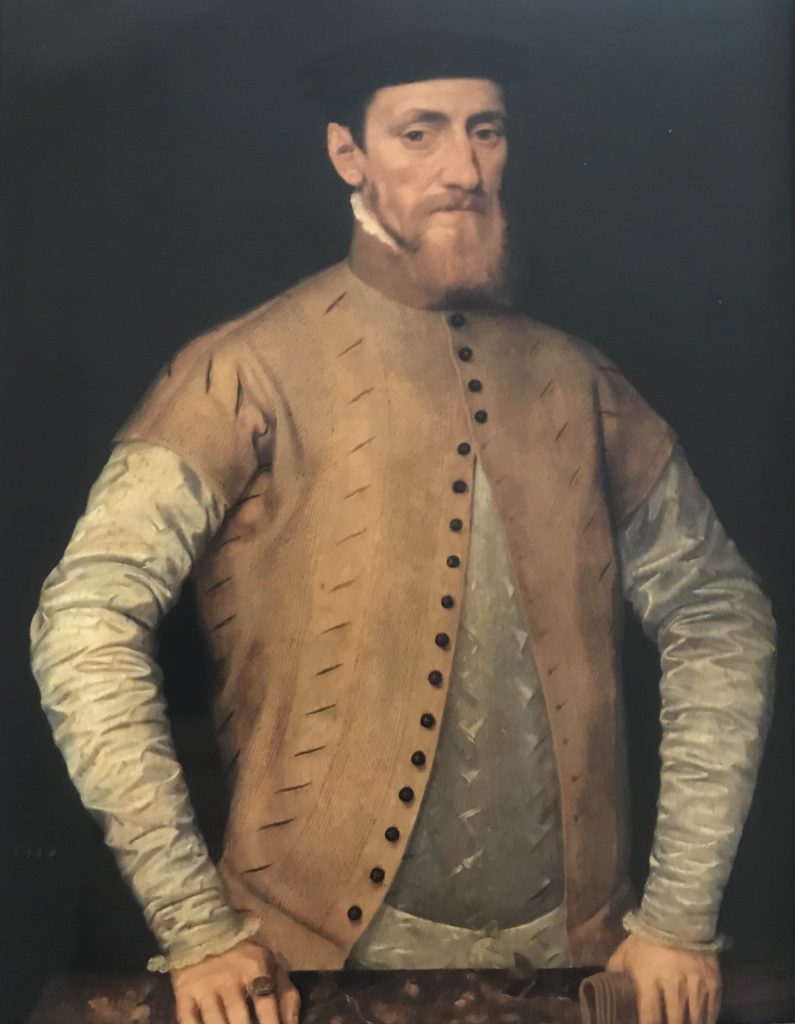

For this, we have to go back to the Civil War, Commonwealth and Restoration of the 1640s, 1650s and early 1660s to explore the work of Sir George Downing:

The source of the above paining is from the Harvard Art Museum, and the image title is “Portrait of a Man, probably Sir George Downing (1624-1684)”. It is often difficult to be absolutely certain of those depicted in paintings of some age (see my recent post on the Gresham’s).

The record for the painting states that on the stretcher is written “Sir George Downing Bart./ born August 1623–Embassador [sic]/ to the States General 1659-Son of/ Emmanuel Downing & Lucy Winthrop/ 4th daughter of Adam Winthrop-/ The nephew of John Winthrop/ Governor of Massachusetts–His/ diplomatic services…[illegible]… are well known to history.”, which does add some confidence that this is Sir George Downing.

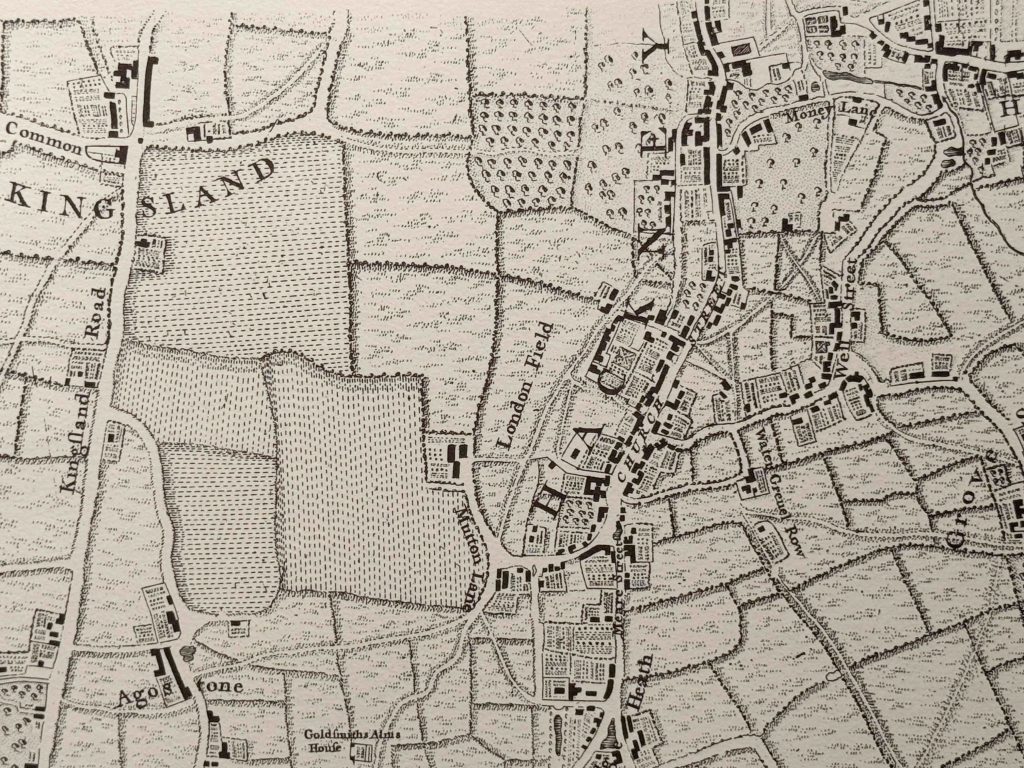

George Downing was born in Dublin around 1623 or 1624, His father was Emanual Downing, a Barrister and Puritan, and his mother was Lucy Winthrop, the sister of John Winthrope who was the Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, an English settlement on the east coast of America which had been founded in 1628.

This family relationship with Massachusetts resulted in the family moving to the colony in 1638, where they settled in Salem.

Harvard College had been founded by the Massachusetts Bay Colony on the 18th of October 1636, and was the first college set-up in the American colonies.

The name Harvard comes from John Harvard who was an English Puritan minister and benefactor of the college, which included leaving his library of 400 books and half of his estate to the new college.

George Downing attended Harvard College, and was one of the first group of nine who graduated from the college in 1642.

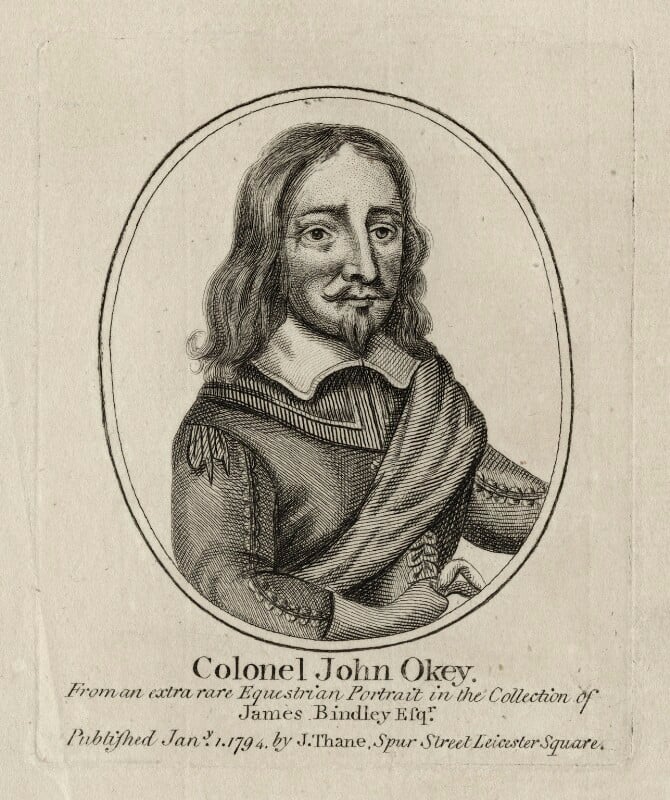

After Harvard, Downing moved to the West Indies where he became a preacher, and in the early 1640s he returned to England, where he found the country in the middle of a Civil War, and he quickly aligned with the forces opposing King Charles I, joining the regiment of Colonel John Okey as a chaplain.

Downing was fully supportive of the actions of Cromwell and the New Model Army in the defeat of the Royalist cause, and he was recognised and promoted quickly to become Cromwell’s Scoutmaster General in Scotland, a role that was basically the head of a spying and intelligence operation, attempts to infiltrate Royalist plots and to turn Royalist supporters to the Republican cause.

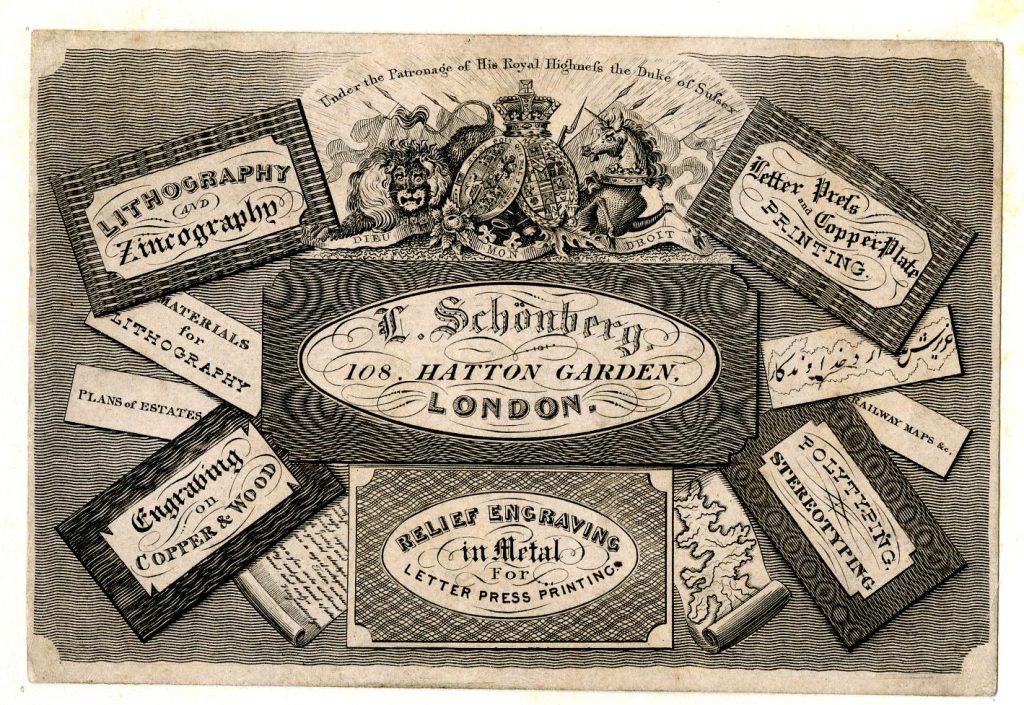

During the years of the Commonwealth in the 1650’s, Downing’s skills became valuable in the diplomatic service, and he became the Commonwealth’s ambassador to the Netherlands, where he also developed a network of spies, and passed information on Royalist plots back to John Thurloe, who was Cromwell’s main spymaster.

The later part of the 1650s were a difficult time for the Commonwealth, the main issue being what would happen to the Commonwealth after the death of Oliver Cromwell. Who would succeed Cromwell, how would such a decision be made, could Cromwell take on the role of a monarch and make the head of the Commonwealth a hereditary title?

Downing supported and urged Cromwell to take on the role of a monarch along the lines of the old constitution that had existed before the execution of King Charles I.

To those holding senior positions in the army and the Commonwealth, it must have seemed that the Commonwealth was in a strong position, the country would remain a Republic. Monarchist plots and uprisings had been supressed, and the future King Charles II seemed to be in a weak position in exile on the Continent.

It was then surprising how quickly after Cromwell’s death, that the whole structure of the Commonwealth collapsed so rapidly, and King Charles II was restored as the monarch of the United Kingdom in 1661, just three years after the death of Oliver Cromwell.

George Downing had been watching how sentiments towards the monarchy were changing and started to plan how he would survive and prosper after the restoration.

This involved actions such as ingratiating himself within the court of the future Charles II, passing information on to the Royalists and claiming that he had been drawn in to the Republican cause rather than being an active initiator of the Civil War and the execution of King Charles I.

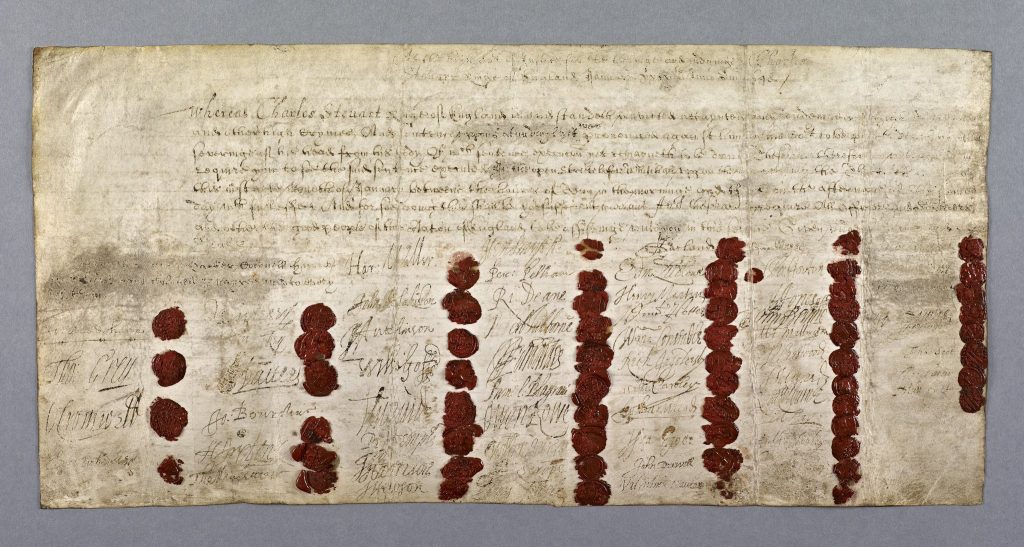

Whilst Downing had supported the trial and execution of the former king, he was not a judge or participant in the trial, and did not sign the execution warrant of the king:

Source: See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Which is an important lesson if you are involved in any plotting or support of a controversial cause – never leave anything in writing.

Despite his involvement and support of the Republican cause, Downing’s efforts to show support for the monarchy were such that after the restoration of the monarchy, he was knighted, and continued in his role as the ambassador to the Netherlands, and it was in the following couple of years that he was to really show his ruthless streak and what he would do to further his own power, position and wealth.

Regicides

After the restoration, the monarchy turned their anger on those who had been involved in the trial of King Charles I, who had signed his execution warrant, or who had had a significant role in his execution.

Known as the Regicides, those who had been responsible in some way for the execution of the King were exempted from the Indemnity and Oblivion Act of 1660, an act that gave a general pardon for all those who had committed a crime during the Civil War and the Commonwealth (other than crimes such as murder, unless covered by a licence from the king, witchcraft and piracy were also not covered by the general pardon).

A number of the Regicides had already died, including Oliver Cromwell and Henry Ireton. Others gave themselves up in the hope of a fair trial and avoidance of a traitors death, whilst others fled abroad in fear of their lives.

Three of those who fled, and who would meet their deaths through the actions of George Downing, were:

John Okey

John Okey had been born in St. Giles, and like many others who were part of the Parliamentary / Republican / New Model Army forces opposing the king during the Civil war, Okey had enlisted in the army, rising through the ranks to become a major, then a colonel, of a regiment of dragoons (mounted infantry).

George Downing had joined Okey’s regiment as a chaplain, and was well known to Okey.

When Charles I was brought to trial, Okey was one of the 80 who were actively involved in the trial, and attended on most days, and the action that would infuriate the restored monarchy was that he was one of the 59 who had signed the warrant for the execution of the king.

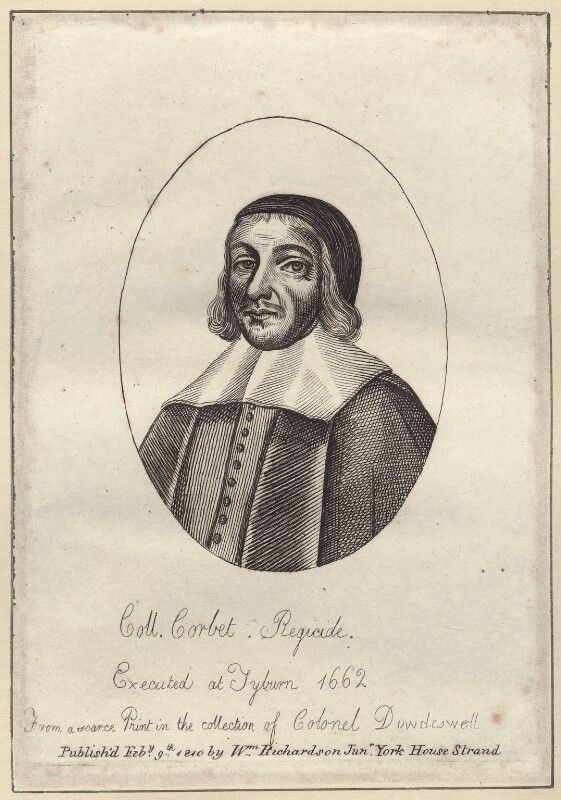

Miles Corbet

Miles Cobet was the MP for Yarmouth and also a Lawyer.

The print of Corbet shown above has the abbreviation Coll. in front of his last name. This may have been an honorary titles, as he did not serve during any military actions during the Civil War. He was though one of the founders of the Eastern Association, which was a military alliance formed to defend East Anglia on behalf of the Parliamentary forces, and he also served as an army commissioner in Ireland, responsible for overseeing the affairs of the army, and with allocation of land within Ireland to soldiers as reward for their service, and often in lieu of wages.

His role in the trial of Charles I was as part of the High Court of Justice, and as one of those who signed the execution warrant.

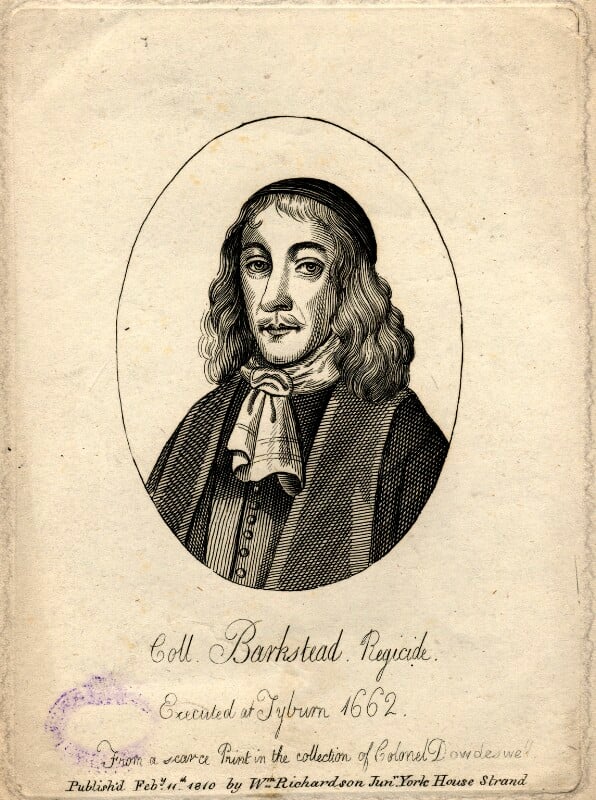

John Barkstead

John Barkstead was originally a goldsmith in the Strand, but who joined the Parliamentary forces, becoming a captain of a foot company in the regiment of Colonel Venn. He was Governor of Reading for a short time, commanded a regiment at the siege of Colchester, and was appointed as one of the judges at the trial of Charles I.

He also signed the Warrant for the Execution of Charles I.

He was appointed Lieutenant of the Tower of London, but used this position to further his own wealth by extorting money from prisoners and generally running a cruel regime.

He was rumoured to have hidden a large sum of money in the Tower of London, and in 1662, Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary that he was busy in a discovery for Lord Sandwich and Sir H. Bennett of the cellars of the Tower for this hidden money.

By signing the warrant for the execution of the King, Okey, Corbet and Barkstead had also signed their own death warrants, as this would be their fate – a public traitors death in London.

Escape and Capture

In fear of their lives, with the restoration of the monarchy, Okey, Corbet and Barkstead fled to Europe, with Okey and Barkstead making their way to Hanau in Germany, where they were accepted by the town and given a level of protection. Corbet had made his way to the Netherlands where he was in hiding.

For Barkstead, Hanau seemed a natural, long term home, as the town was well known for the manufacture of jewellery, and Barkstead’s background as a goldsmith in the Strand would come in use.

As Hanau seemed to be a long term home for Okey and Barkstead, they wanted their wives to join them, and a plan was put together for them to meet their wives in the Netherlands, from where they would all travel back to Hanau.

They believed that they would be safe in the Netherlands and had assurances that Downing had not been given any instructions to hunt for them. The Netherlands was also known for tolerance and for putting commerce before any other concern.

They travelled to Delft, and met up with Corbet, who was keen to meet with some friends after his time in hiding.

Downing meanwhile had been putting together plans for how he would find and capture any regicides that were living or passing through the Netherlands. He was worried about the repercussions of capturing any regicides and transporting them back to London without the approval of the Dutch, and he had problems with getting an arrest warrant from the Dutch authorities.

After much persuasion, Downing received a blank arrest warrant, which he would be able to use against any of the regicides that he could discover in the Netherlands, and it would soon be put into use.

Through Downing’s network of spies, he discovered that Okey, Corbet and Barkstead were all in Delft, and just as they were about to split up, Downing and his men pounced on the house, and found the three sitting around a fire, smoking pipes. and they quickly rounded up the three regicides. They had their hands and feet manacled and were thrown in a damp prison cell, whilst Downing finalised their transport back to England.

Whilst they were in captivity, the three were visited by Dutch politicians who assured the three that they would be freed, however Downing used his skills to threaten and bully the Dutch on the possible consequences of such actions, and the Dutch conceded, and let Downing continue to hold the three and arrange their transport.

Another challenge was the Bailiff of Delft who was not cooperative and threatened to derail Downing’s plans. Downing’s response to this was another indication that he would do anything to have his way. He made inquiries about the bailiff and learnt that “he was one who would do nothing without money”, so Downing offered him a bribe – a reward if he would keep the prisoners safe until they were finally in Downing’s hands.

There were other problems. The magistrates of Amsterdam sent a message to the authorities in Delft that they should “let the Gates of the prison be opened and so let them escape “.

The bailiff warned Downing that the “common people might go about to force the prison and let them out”, and the authorities in Delft made efforts to provide counsel for the regicides.

Downing finally received an order from the Dutch authorities addressed to the bailiff in Delft to release the prisoners to Downing. The bailiff was concerned that there would be a rising “if there were but the least notice of an intention to carry them away”.

Downing had already arranged for an English frigate to be available, and with the aid of some sailors from the frigate, and a small boat, he:

“resolved in the dead of the night to get a boate into a litle channell which came neare behinde the prison, and at the very first dawning of the day without so much as giving any notice to the seamen I had pro

vided . . . forthwith to slip them downe the backstaires . . . and so accordingly we did, and there was not the least notice in the Towne thereof, and before 5 in the morning the boate was without the Porto of

Delft, where I delivered them to Mr. Armerer . . . giving him direction not to put them a shoare in any place, but to go the whole way by water to the Blackamore Frigat at Helverdsluice.”

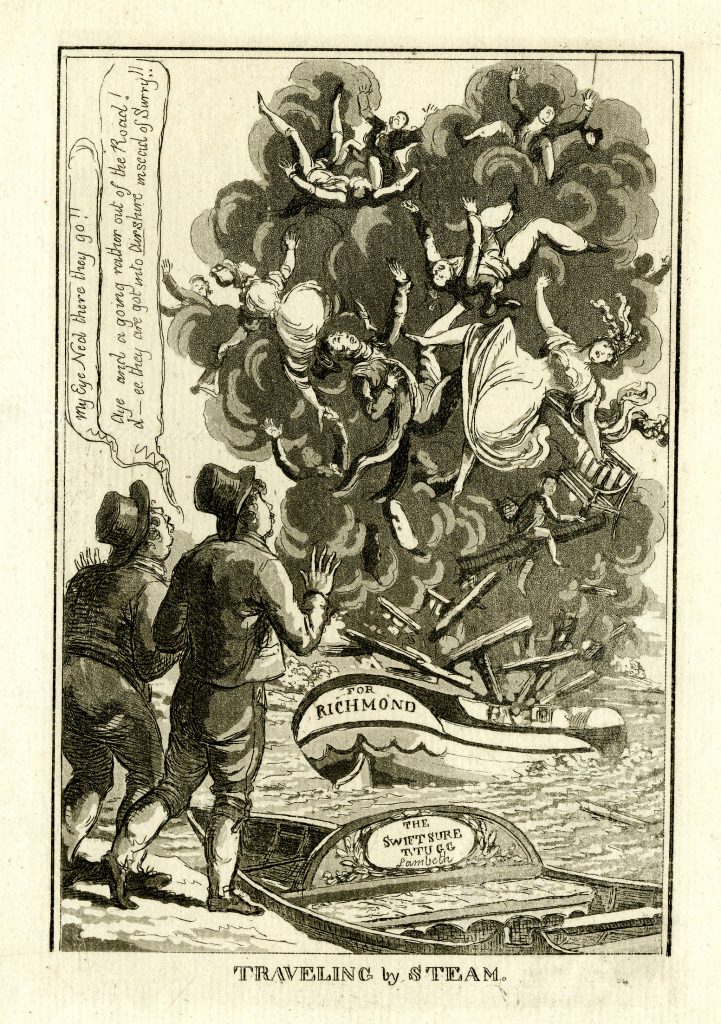

The Frigate Blackamore carried the three prisoners back to England, where they were imprisoned in the Tower awaiting a trial, which was not really a trial as in the view of Parliament and the Monarchy, they had demonstrated their guilt by fleeing the country. The trial was a formality to confirm they had the right people.

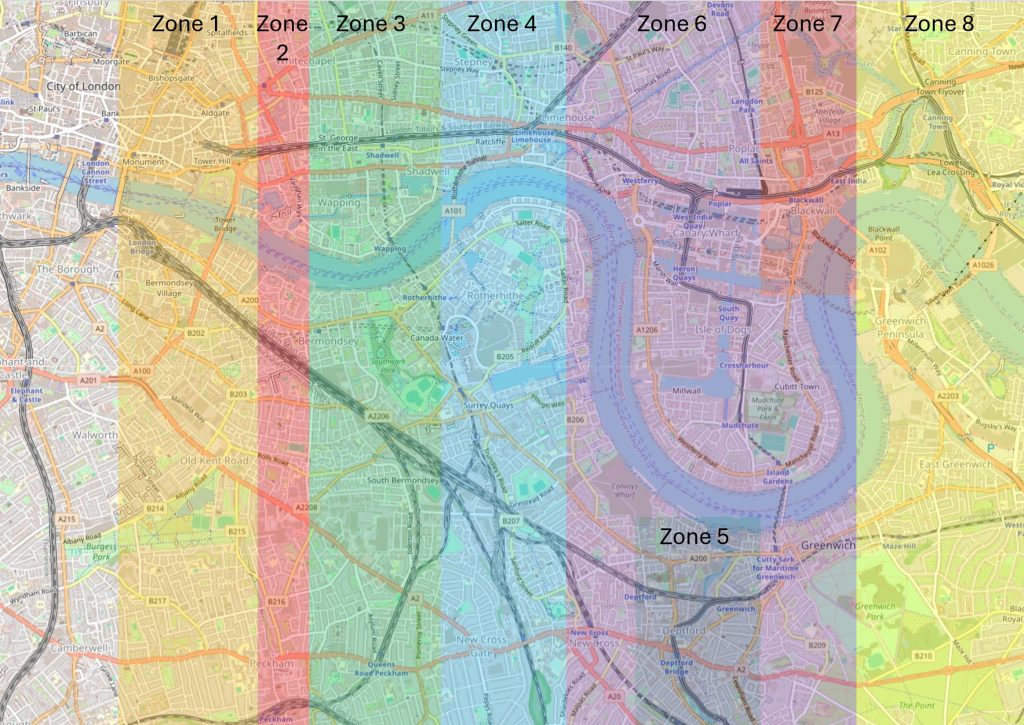

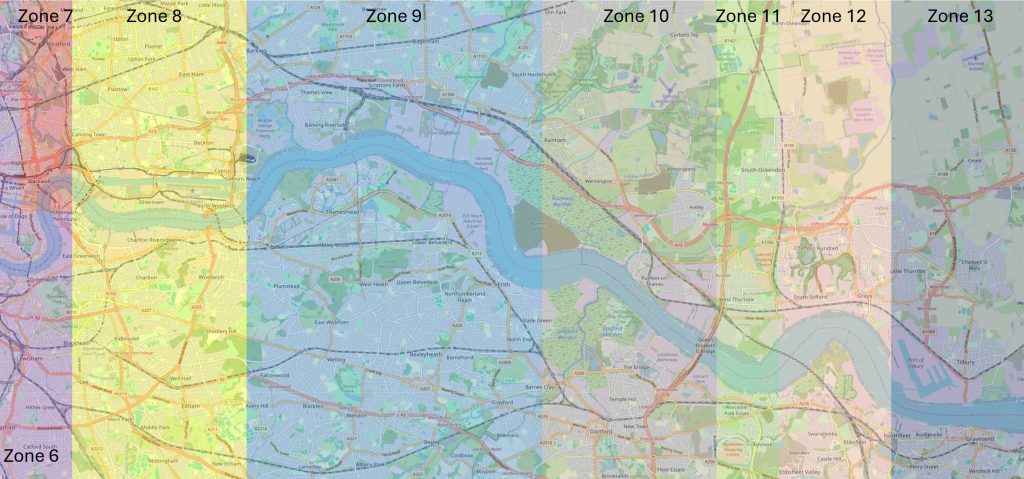

Having been found guilty of treason, on the 19th of April 1662, the three men were transported from the Tower to Tyburn, each tied to a separate sledge as they were drawn through the crowds, with much mocking abuse from Royalists. Barkstead left the Tower first, a place where he had once been the Lieutenant, and raised his hat to his wife who was waving from a window.

On arriving at Tyburn, each man gave a speech to the crowd, and were then put on a cart under the gallows. When they were ready, the cart was pulled away, and they hung for 15 minutes, before being taken down, and were then drawn and quartered, all in front of a large crowd.

Barkstead’s head was placed on a spike overlooking the Tower of London, mocking his former role at the Tower.

Before his death, Okey had sent a message of obedience to the restored monarchy, and as a reward for this, his family were allowed to bury his mutilated body in a vault in Stepney, however a large crowd gathered around Newgate where his body was being held, and fearing that this was a show of support for a traitor, the King swiftly changed his mind, and Okey’s body was hastily buried in the grounds of the Tower of London.

After the Regicides

Downing appears to have shown very little if any remorse or regret for his actions in the capture and execution of his three former colleagues, especially Okey, in whose regiment Downing had once served during the Civil War.

He acquired large estates and properties across the country and in London. He was one of the four Tellers of the Receipts of the Exchequer. He inspired the Navigation Act: “the foundation of our mercantile marine, and consequently of our navy, and consequently of our colonies and spheres of influence. He was also the direct cause of the Appropriation Act, an Act indispensable in every session, for government at home and one which has been appointed by all our self-governing colonies,” and he was instrumental in persuading the Dutch to exchange New Amsterdam, their colony on Long Island, for the British colony of Surinam in South America. New Amsterdam was then renamed as New York.

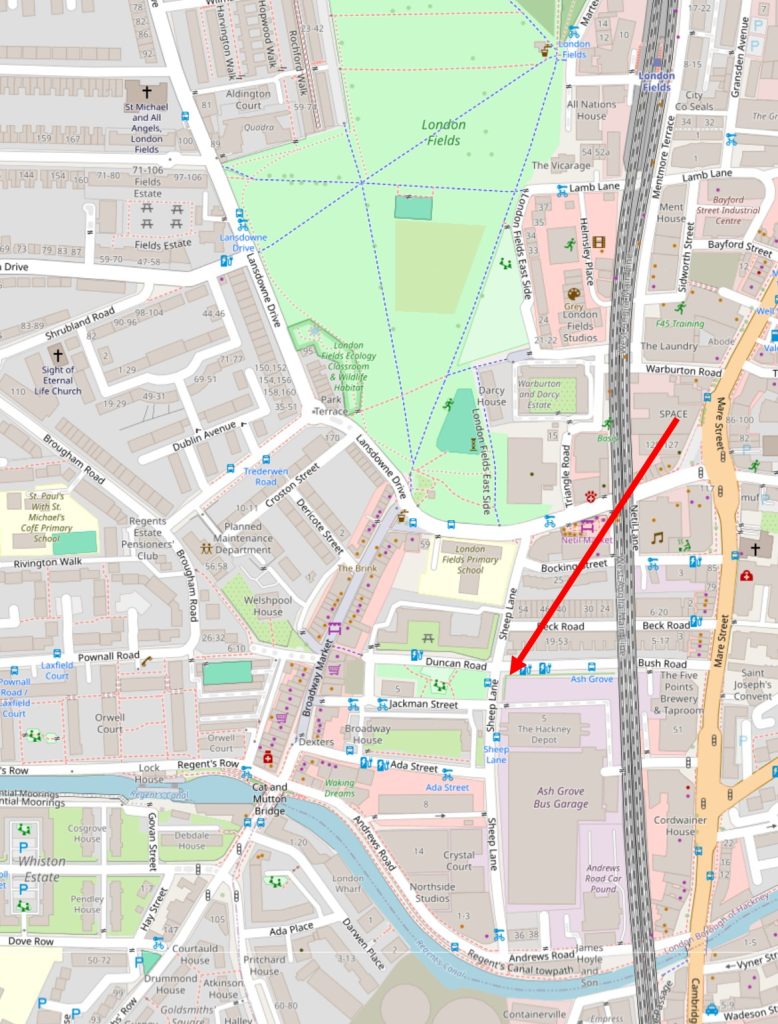

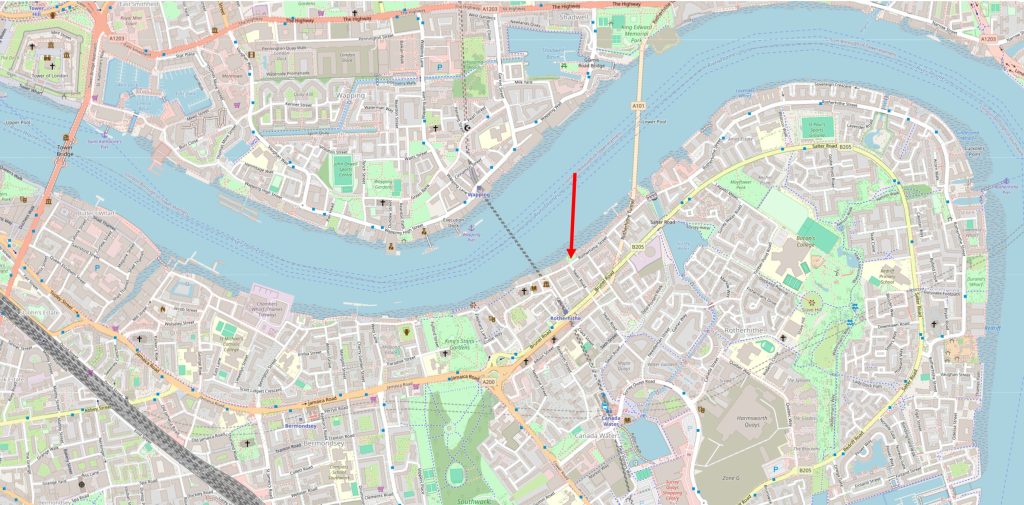

George Downing owned land near Westminster, and when the leaseholder died in 1682, Downing developed a cul-de-sac of more than twenty plain, brick built, three storey terrace houses, and he petitioned Charles II for permission to name this new street Downing Street.

Royal approval was granted, but he did not live to see the completion of the street as he died in July 1684 when he was 60, two years prior to work was finished.

The general view of Sir George Downing was that whilst clever, quick to action, ambitious and a very hard worker, he was also self serving, would shift his allegiance depending on changes in political and royal power, and as demonstrated with Okey, Corbet and Barkstead, this would also include the betrayal of his former friends and colleagues.

After the restoration, there were many who recognised Downing’s true character. After the capture of the regicides, Samuel Pepys’s wrote in his diary:

“This morning we had news from Mr. Coventry, that Sir G. Downing (like a perfidious rogue, though the action is good and of service to the King, yet he cannot with any good conscience do it) hath taken Okey, Corbet, and Barkestead at Delfe, in Holland, and sent them home in the Blackmore.”

Downing – a name associated with self perseveration to the extent that former colleagues and the cause for which they all worked, were betrayed, and now recorded in the name of the street where the Prime Minister resides.

Sources: I have been reading a number of books about the Civil War recently which I will list in a future post. My main source for the actions of Downing in the Netherlands and the capture of Okey, Corbet and Barkstead is from “Sir George Downing and the Regicides by Ralph C. H. Catterall in The American Historical Review, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Jan., 1912), and published by the Oxford University Press“.

Resources – The World Turned Upside Down

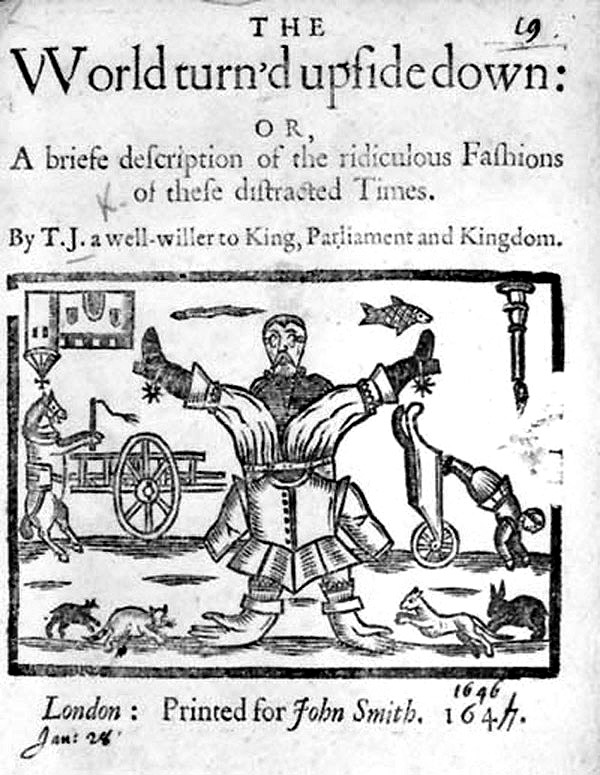

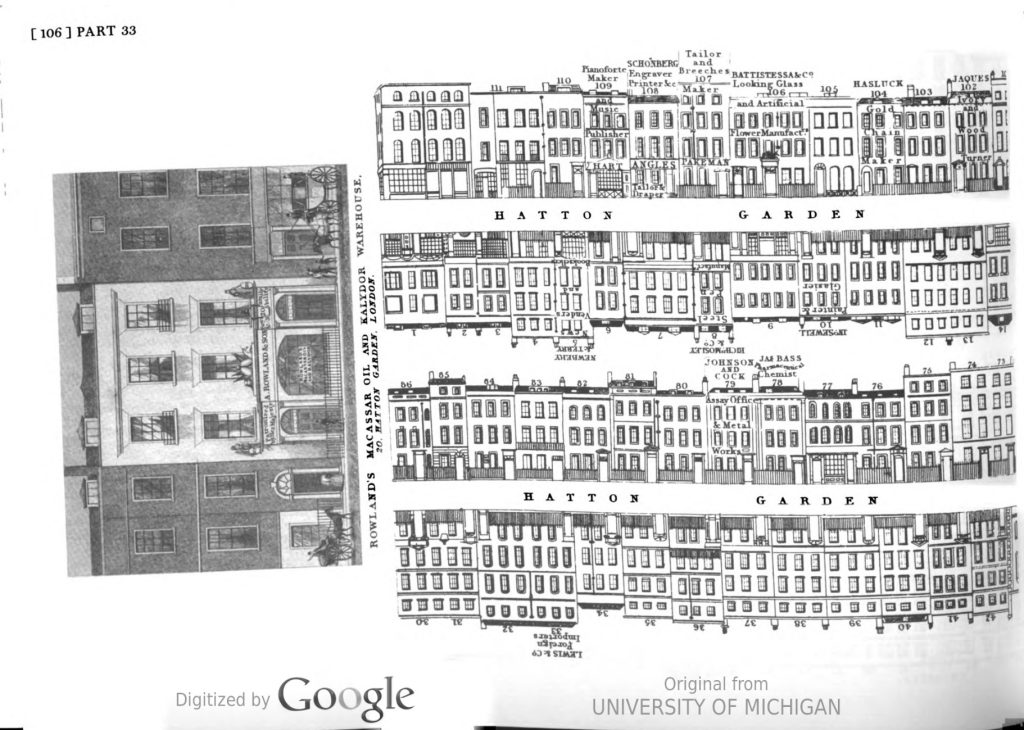

As today’s post is the first of a new month, it is a post where I cover some of the resources available if you are interested in discovering more about the history of London.

As today’s post has been about the fate of three of the regicides involved with the trial and execution of King Charles I, and George Downing, who supported both the Parliamentary cause and then swiftly converted to support the monarchy, today’s resource is a brilliant website full of resources covering everything Civil War, and events in London played a very significant role, not just during the Civil War, but the lead up to, the causes of the war, the Commonwealth and Protectorate, the people, politics and religion, the restoration and later impact.

The website is The World Turned Upside Down:

The name of the website comes from the title of an English ballad published in the mid 1640s, when Parliament was implementing policies that tried to ban the more traditional celebrations of Christmas that the more Puritan and to an extent Baptist members of Parliament believed were associated with the Catholic religion, and that Christmas should be a more solemn event, without the drinking, feasting and joyous elements of the traditional Christmas:

Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The standout feature of the website are the podcasts. There are currently 112 on the site with more being gradually added (you can sign up for alerts). Each podcast explores a different aspect of the Civil War and is by an expert in the subject.

For each podcast there is also a transcript, glossary, timeline, maps and further reading.

The first four podcasts in the list are shown in the screenshot below:

There is so much in the news about the destructive elements of social media, AI and the Internet, but the World Turned Upside Down is one of those sites that restores your faith in what the Internet can deliver when a community of real experts put together such a resource – which is freely available.

Even if you have only a passing interest in the mid 17th century and the Civil War, the site and podcasts are well worth a visit, and again, the link to click for the site is: The World Turned Upside Down